Evaluation of extra-limital movement in the Large-billed Tern

10 Evaluation of extra-limital movement in the Large-billed Tern

An evaluation of the extra-limital movements of a South American species having been well documented serves as a good demonstration and example of a pattern which I similarly attribute to the Andean Condor. The Large-billed Tern Phaetusa simplex has been recorded throughout North America as a vagrant. Such records of its dispersal away from its principal breeding distribution of the Amazon basin date back to 1908 and, in the United States, to 1949. In addition to having been reported in the United States, the Large-billed Tern has also been recorded in Chile, Clipperton atoll, Panamá, Nicaragua, Grenada, Trinidad and Tobago, Cuba, and Bermuda.

Further review of its movements add the following to this list: Ecuador (former breeding in western provinces, extirpated), Costa Rica, Honduras, Margarita and other offshore Venezuelan islands, and Aruba.

RECENT REPORTS FROM FLORIDA

The Large-billed Tern also deserves consideration in wake of the recent reports of no fewer than two separate individuals, cases of vagrants, in different parts of the state of Florida. The ongoing observations of each of these terns mark the first instance of the genus in the United States in thirty-five years. The matter came to my attention the day after both of these sightings, which, in different areas of the state, happened to be concurrent; just glancing at the image from the American Birding Association website (Kyle Matera) without yet reading the details, I at once recognized the deep yellow of the large, oversized beak of this bird, its black cap falling over the eyes, and the black remiges as telltale signs that representatives of this enigmatic species had been sighted a continent away from their breeding grounds.

Phaetusa simplex chloropoda in Florida: 2023

Brevard Co. June 1–11, 15, 17–18, 22; July 1 [erroneous]; Aug. 24

Indian River Co. (perhaps same individual as for adjacent Brevard Co.) July 1–2, 4–7, 13–17, 20–21, 27–28; August 8; September 16

Collier Co. June 1–7, 9–11, 13–14, 16, 18, 21–25, 27–28, 30; July 2–4, 6–9, 14–19, 21–24, 26, 28–29, 31; August 1–2, 5–7, 9–21, 23, 25–31; September 4, 7, 10–13, 18–19, 21, 23–24, 26–27, 29; October 2

https://www.aba.org/rare-bird-alert-june-2-2023/

The individual in Brevard County, Florida, shows bright yellow and in my opinion is the subspecies P. s. chloropoda.

There is at least one bird in Collier County, Florida, which is still being reported. (For about a day, there were originally two of them.) This continuing bird has a noticeable darker gray on its back and also a dusky tip on its yellow beak. The black of the cap is limited to the hindcrown with some indistinct gray on the crown itself.

Though the International Ornithological Congress now recognizes this species as monotypic, it is useful to consider the provenance of birds from remote areas of South America, and much of the population occurs in the southernmost part of its distribution (Cornell Lab, “Birds of the World”).

Prior Reports from the United States

New Jersey, 1988 (May 27–30) Hudson County, Kearny Marsh

https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/nab/v043n05/p01275-p01276.pdf

It is suggested that the New Jersey sighting was of the chloropoda subspecies, and it had a paler back; however, as their assessment was not categorical to chloropoda, they assert that the previous sightings in the United States refer to the nominate form.

This vagrant, an adult, was photographed in color by P. A. Buckley.

Ohio, 1954 (May 29) Mahoning County, Evans Lake

https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/nab/v033n05/p00727-p00727.pdf

The sighting in Ohio was of a bird with a “yellow” beak and a darker back; it is not clear to what subspecies it is referring.

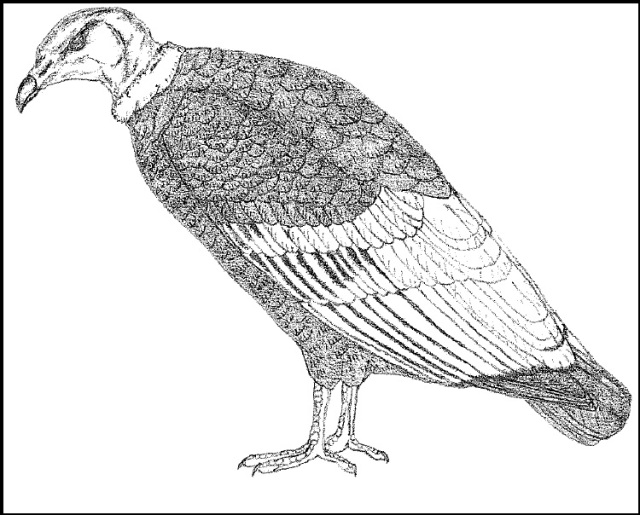

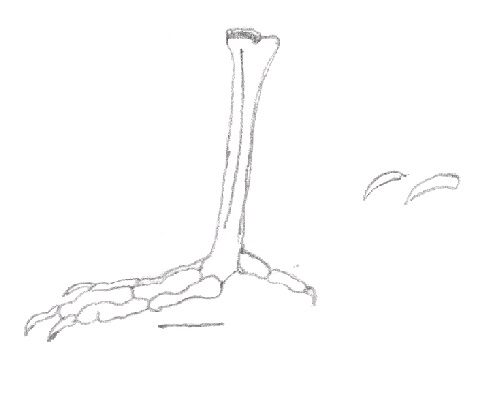

A drawing was supplied by Vincent P. McLaughlin

Illinois, 1949 (July 15–about July 24) Cook County, Lake Calumet

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/318407#page/370/mode/1up

The Lake Calumet sighting in Illinois was a bird of the subspecies P. s. chloropoda, which occurs in the southernmost part of its distribution in Argentina and southern Brazil and shows paler gray above and primuline yellow on the beak and feet. This was the first record of a living, vagrant Large-billed Tern.

The illustration was by Richard Zusi. The individual appears to be a non-breeding bird based on the sketch therein (page 4).

“How the tern got to Chicago is anybody’s guess. Robert Bean of the Brookfield zoo, and Fred Meyer of the Lincoln Park zoo, declare that it was not an “escapee” from their collections. It might have been carried across the Caribbean by wind currents and continued up the Mississippi and Illinois river valleys to the Calumet area. The habitat is similar to its native one–it’s just on the wrong continent.” (Janet H. Zimmermann, The Audubon Bulletin [Illinois Audubon Society], 71:5)

PATTERNS

These records show an obvious pattern, that the Large-billed Tern is given in its extreme extra-limital movements to occur during the northern late spring and early summer. As of writing, the individual in Collier County, Florida (Eagle Lakes Community Park), is still present, well into the beginning of autumn, though its initial arrival conforms well to the argument. The following accounts from elsewhere are also consistent.

_________________________________________________________________________

REPORTS FROM BERMUDA, THE CARIBBEAN, AND CENTRAL AMERICA

Bermuda

There is also a Bermuda specimen collected by David Wingate in 1961 (June 4 (or June 14th) at Spittal Pond.

Cuba

A living example of the Large-billed Tern was reported on April 8, 2019 in Cuba’s southern coast in the town of Guanimar (Artemisa province). Garrido and Kirkconnell in Field Guide to the Birds of Cuba (2000) provide two other records of it, prior to their publication, however these include one specimen which was not dated. The other, also a specimen, was dated May 28, 1910. It is not clear which subspecies was represented by any of these three, yet it is significant to note the close proximity of the country to the southern tip of Florida.

Aruba

As with other information I have ascertained about the species’ extra-limital movements, I have heavily consulted eBird (www.ebird.org) to better understand the subject. Another valuable resource is the research report published in the Journal of Caribbean Ornithology (24(2):75) by Anthony White and Anthony Jeremiah. Not far from the northern tip of South America is the island of Aruba, which, due to its proximity to the distribution and habitat of the more northerly, nominate subspecies of this tern, yields just one record of its occurrence, that of a specimen which was collected May 12, 1908. It is not clear to me if this skin is, indeed, of the nominate subspecies, but it may be worth considering that it could be.

Grenada

On the southern tip of the island, an individual was seen and photographed. It was present May 31, 2010 and the following day. The details of this find were published in White & Jeremiah (see above). The authors state that the sighting was the eleventh of such reports of the Large-billed Tern away from either Panamá or coastal South America. Having seen the images of the individual from Grenada, and I am unable to determine how bright is the yellow of the beak, nor do the images give a clear view as to the paleness of the gray of the back. As with the Aruba specimen, I can suspect that it may be a representative of the nominate subspecies given the proximity of the island to the northern part of the main continent where P. s. simplex is resident.

See also North American Birds (64(3):512, with black-and-white images, and 64(4):657) for more information.

Honduras

On April 28, 2003, one was identified as far north as Honduras. This bird was seen on the coast of Gracias a Dios department in the northeast section of the country and situated along the Caribbean Sea. North American Birds 57:415 is the source which I consulted.

Costa Rica

The same source for Honduras also lists a first report for Costa Rica, where one was seen Río Tortuguero Lagoon (Limón), March 10–15, 2003. This was not the same individual, but the location is also located on the Caribbean side of the country. (Depending on the source, there may be some confusion as to the year of record for this as well as the Honduran sighting; neither occurred during 2002.)

The Large-billed Tern was also seen in Costa Rica, also along the coast of the province of Limón, on June 13, 2007. (Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 130(4):240.)

Nicaragua

The earliest report from Nicaragua dates to December 8–10, 2012 on the southern Caribbean coast of the country. There were also reports the following year, on August 3–4 and August 11, 2013, along the shores of Lago Cocibolca. Having become familiar with an image of one of these vagrants sighted along this latter locality, I can see that the back is dark, not pale, gray, and, therefore, it represented the nominate subspecies. It was in non-breeding plumage.

Panamá

The date of the earliest record of Phaetusa from the Republic of Panamá is, ironically, recent, much more so than those for the United States or Cuba. Along the Río Matasnillo an individual was seen on August 18, 1984 by Howard Laidlaw. A quarter of a century passed before the next was sighted, but not photographed, on Gatún Lake, on February 26, 2009. Near the Gulf of Parita, which is on the Pacific side of the country, another was seen, on April 11, 2011. A storm was the likely cause of the appearance of a flock of fourteen terns which passed by Palmas Bellas on August 18, 2012.

There is a record of one along the Río Chagras dated February 29, 2016. It was along the same watercourse, the following year on February 14, that a Large-billed Tern was actually photographed in Panamá for the first such instance. It was a non-breeding tern with an off-yellow beak and a dusky gray back. I wonder that perhaps it was the same recurring individual that had been reported, but not photographed from the previous year? Clearly it shows that this vagrant was of the nominate race. It was present to at least March 30, 2017.

During the same month, another bird was seen on the country’s southern coast, the Calzada de Amador, on February 18. Two individuals were photographed together on La Jagua marsh the following summer (August 19–September 3), and they were in non-breeding plumage and show bright yellow beaks and pale gray backs; I will go so far as to ascribe these as representative of the subspecies chloropoda, although no prior discussion suggests my identification.

A bird was described as having a beak that was “amarillo pálido y grande” near to the Gulf of Parita on August 7, 2020. However, the coloration of the back was not mentioned, and I cannot assume to which subspecies it belonged. Last winter, there was what is now the most recent sighting of one in the county, along the Río Chucunaque, on February 16; the area is close to the border with Colombia, where many of these terns are resident.

Trinidad and Tobago

They are regularly found as a resident genus on Trinidad, where terns were collected there from 1903, but the earliest report of a sighting of a living one on Tobago dates back only to June 10, 2012.

________________________________________________________________________________

SOUTH AMERICA

Isla de Margarita, Isla de Coche, and Isla La Tortuga (Venezuela)

Non-breeding terns have been reported on Isla de Margarita since 1987, and other records have emerged dating from the following years: 1994–1996, 2000, 2010, 2014–2016, 2018, and 2021–2022.

Ecuador

In the western, coastal area of Ecuador it may occur, but no longer as a breeding species as it has been extirpated there. However, according to the SACC (South American Classification Committee), it is still a resident species in the country.

Chile

The provenance of a specimen from San Antonio is questionable. It was allegedly collected from this central province of Chile and was dated August 17, 1872. In Chile the Large-billed Tern is listed as Hypothetical by the SACC. However, there is a CONFIRMED eBird report from March 16, 2009 of a sighting of at Azapa Sobraya (Arica province).

This accounts also for information provided by VertNet (portal.vertnet.org).

[Clipperton atoll

Clipperton atoll is a remote island located some distance from the southern Pacific coast of México. There are no records of the Large-billed Tern from this island. The presence of one, so far north as this from its main distribution, would be remarkable. I will mention it here as I was given to erroneously believe that such a record did exist. I can also see how some sources can be misleading, in their prose, by mentioning the tern along with information about another species, the Dark-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus melacoryphus, which was reported from Nicaragua and has been established as a vagrant to Clipperton.

https://ebird.org/camerica/news/new-species-for-ebird-central-america-dark-billed-cuckoo

I consulted the journal Condor (66:357, Stager (1964)), and there is no reference therein to the genus Phaetusa.]

_______________________________________________________________________________

BREEDING DISTRIBUTION

Phaetusa simplex nests throughout South America in Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Guyana, Suriname, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina. I also recognize, contra the SACC, that it nests in French Guiana and is not simply a non-breeding visitant; many sources reinforce this view.

To recognize two races, as I do, would place the boundary of these as follows.

Sterna [Phaetusa] simplex J. F. Gmelin

The distributional areas of South America in the Amazon and Orinoco basins north of those of which subspecies chloropoda would be found. It excludes the Andes.

Sterna [Phaetusa simplex] chloropoda Vieillot

Basins of Río Paraguay and Río Paraná to northern Argentina. In addition to Argentina, this also includes the genus’ entire southern breeding distribution.

(In being comprehensive, I will also remark on the names given to this species which are no longer valid. They all were originally placed in Sterna and in the early nineteenth century. They are brevirostris Vieillot, magnirostris Lichtenstein, and “speculifera” Lesson, the last being a name of doubtful ascription (Catalogue of the Birds in the British Museum, 25:23). The importance of these three names lies in an evaluation of the respective descriptions of each of them and may yield further argument as to an association of plumage variation to geographic distribution.)

The races are regarded as clinal by the International Ornithological Congress (2014), and, thus, Phaetusa is now being treated as having a single, monotypic species as well as being a monotypic genus. Clinal variation is when populations, in this case those of the Large-billed Tern, show intergradation and, therefore, lack the impetus to be treated separately. Firstly, I feel that there are two populations which are distinctive morphologically and are, thus, separate. Secondly, it may not matter whether it is appropriate to recognize one or two subspecies; it is evident to me that the southernmost birds of the race chloropoda do show this variation, and, as I will explain below in my concluding comments, are largely responsible for the appearance of this species in North America and elsewhere.

In Rare Birds of North America (Howell, Lewington & Russell; 136) the authors discuss subspeciation of the Large-billed Tern. They state that it is “not known to be separable in the field… [E]quatorial breeders average slightly darker upperparts than s. breeders…”

Emmet R. Blake (Manual of Neotropical Birds 1:648) asserted the opposite, that chloropoda represented those birds with darker gray backs. This opinion has not been upheld where the tern has been treated as polytypic.

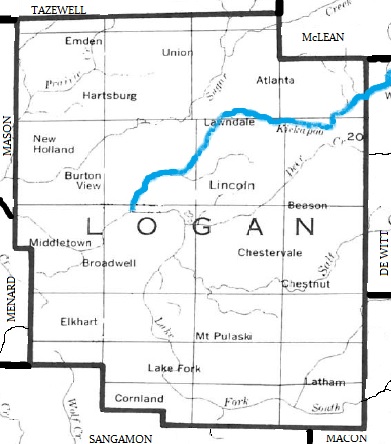

Map of the Río de la Plata. (Karl Musser)

The above map reveals the details of the distribution of the Large-billed Tern Phaetusa simplex chloropoda. In Brazil, this would include the states of Mato Grosso, Goiás, Minas Gerais, and states south of this region not on the Atlantic coast. It would also include the Distrito Federal but, as respects its breeding range, not the states of Espírito Santo and Rio de Janeiro.

MIGRATION

Phaetusa simplex is by its nature a tropical species (much unlike the Andean Condor). It is not necessarily given to migrate, but when the breeding season has concluded they are known to disperse. This dispersal would be to coastal areas throughout much of South America. It is, in that sense, a migratory species. See my comments in the last three paragraphs of this post.

_______________________________________________________________________________

MOVEMENTS OF LARGE-BILLED TERN AS RELATES TO MOVEMENTS OF ANDEAN CONDOR

The above information has revealed many details gathered together on a bird that is not at all like the Andean Condor in habits and appearance other than the fact that it is a distinctive South American avian entity. From the many various records on its extra-limital appearances north of the continent to an evaluation of its variation and debate over whether it is a species that is polytypic, it may be assumed that there is important relevance to that species of diurnal raptor and scavenger which comprises the subject of these posts. There is, as I will explain.

I wanted to write a separate piece about the Large-billed Tern in relation to the Andean Condor because it is to a certain source that I owe some inspiration. That work is the Smithsonian Birds of North America (Fred J. Alsop, ed., (2000)) and the profile of the former species, therein, on page 426. There is a colored illustration of the tern by Svetlana Belotserkovskaya with a map of its distribution in North America, and I found that this latter feature was compelling. Here, this South American bird, which nests only on that continent, had been only known, at the time of the book’s publication, in three states–all of which are in the north of the country–yet no where else. While looking at this book, decades ago, I felt intrigued because I had become familiar with the reports of the “Thunderbird” of Illinois, which I evaluated in a previous post of The Unknown Andean Condor (UAC5). One of the locations where the Large-billed Tern was known was Chicago, very close to the same locality as that of mysterious giant birds.

I am not arguing that the movements of the Large-billed Tern have a direct nor special relationship with that of the Andean Condor. The latter should not necessarily be expected, also, if the tern appears anywhere as a vagrant. The Large-billed Tern, like the condor, is an aerialist. It is given to great movements of flight and covers large distances. However, in the tern there are a multitude of legitimate, authentic records of its extra-limital movement; in the condor, much is wanting by way of substantiating its own records, which motivates me to write about both of them. The southernmost subspecies of Large-billed Tern, P. s. chloropoda, as I have described above, undergoes some type of migration. It is difficult to say whether this holds in the nominate subspecies, but the point is that many of the records of the tern elsewhere, most notably its first record of appearance in the United States, allude to chloropoda, which is intriguing.

It is an irony that those terns which represent this race, and not the nominate simplex, are those subject to the most displacement away from southern South America, occurring in areas that are so far removed from its distribution; whereas, there are actually fewer, if any, records of the nominate in the United States, its distribution including those regions of northern South America which are much greater in area of expanse and which are closer to North America itself. Probably many of the records of its extra-limital movements from the Caribbean islands and Central America will show that the nominate can also be given to some evident vagrancy.

With regards to chloropoda occurring anywhere, these are the terns which are more likely to disperse because they occupy habitats which undergo more seasonal change, particularly in those areas in southern Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Argentina. In their movements, some birds may be given to what is called a misorientation. They may fly towards the more tropical areas of the Amazon during the northern spring, but rather than returning to their original localities, the birds may “err” and go further north. They may continue this way until they reach a suitable stopping point, which may be, as the records make plain, as far as Lake Calumet in Illinois or Lake Evans in Ohio. I find it rather fitting that they may be found there because these areas are in some respects parallel to that of southern South America and are not as tropical. Thus, they disperse until they find a suitable point to stay, by which they can recover. I am given to write another, separate post on this subject because what I provide here is very much a terse summary of what happens, also, with the Andean Condor. For that, I have written about the Large-billed Tern.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Mathew Louis